肿瘤精准医学20年的成就与挑战

浏览量:4750 / 发布时间:2021-11-18

关注“胡迪医学”,了解更多世界医学动态

胡迪主任参考世界顶级杂志《柳叶刀》

期刊社论,编译了这篇推文,

让大家了解肿瘤精准医学20年的发展,

展望精准肿瘤学的发展前景。

肿瘤精准医学的成果和挑战

20年前《人类基因组计划初稿》发表,

从此肿瘤精准医学驶进了发展的快车道。

使用基因分型和基因组学,

已经成为一些癌症标准治疗的一部分,

这是肿瘤精准诊疗的伟大进步。

癌症精准医学已经给一部分病人

带来了癌症治愈,肿瘤分期减期,

明显改善生命质量,

延长总体生存期等医疗结果,

这是生物学家和临床医学家们

共同努力,突破了部分癌症难治的困境。

人们渴望、难以抗拒一种理想,

那就是能够超越难以医治的传统界限,

实现更加精细,更加有效,

“以病人为中心”的诊疗模式。

癌症精准医学不是在路上,

而是已经来到我们的身边。

肿瘤精准医学的发展,

逐渐融合了大数据、蛋白组学、

转录组学、分子成像等领域技术。

尽管挑战,但是科学家和医学家们

依然在将这种理想转化为

有意义的、公平的医疗服务。

他们需要时间去解决一系列的、

因为精准医学而产生的新问题,

比如如何消除医疗成本的增加,

如何推广、设计充足的临床试验,

如何更有效地收集、整理各种数据,

如何分析诊疗技术的医疗和经济价值,

如何规范和监督精准医学的应用、

如何解决带来的公平和伦理相关的问题。

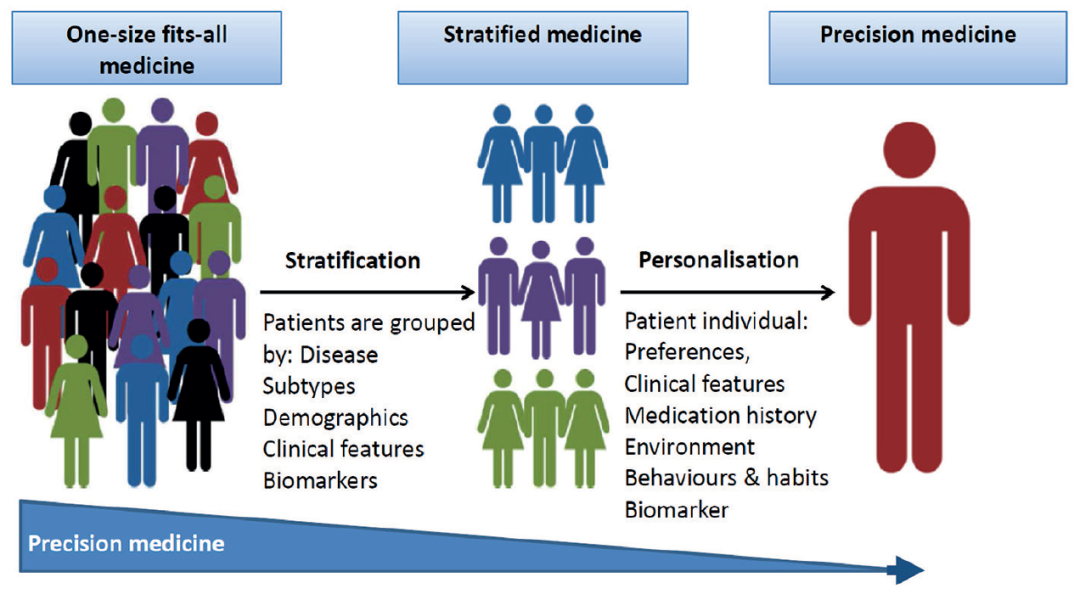

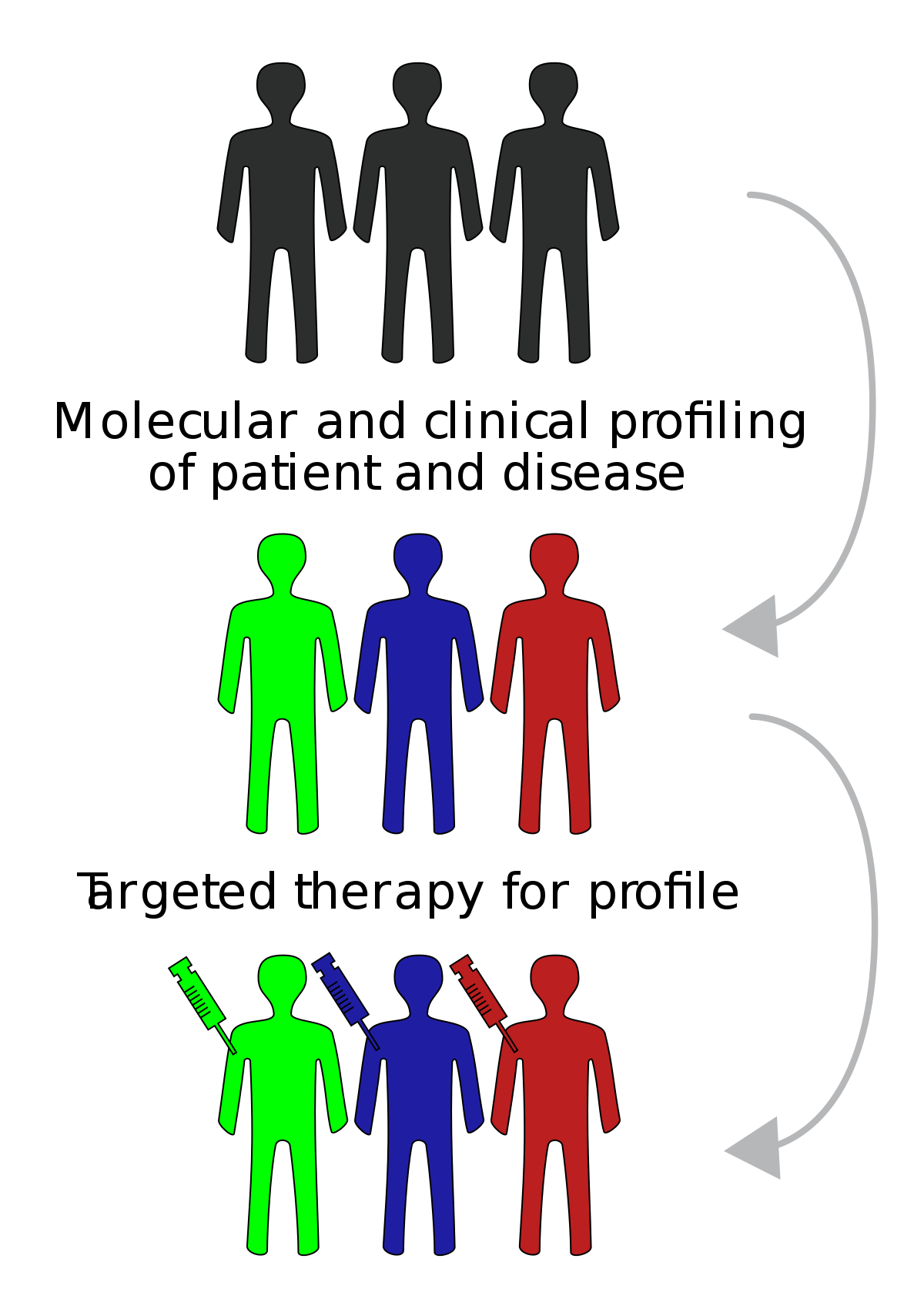

什么是精准医学呢?

美国国家癌症研究所(US NCI)

对精准医学的定义是,

一种利用个人基因、蛋白质

和环境信息来预防、诊断和

治疗疾病的医学形式,但是,

利益相关者的定义大相径庭。

靶向药物治疗临床应用于

许多实体癌和血液癌症,

放疗和手术的精确方法也是如此。

然而,即使有更成熟的基因检测,

转化为临床医疗远远落后于科学发现。

指南推荐的检测经常未得到充分使用,

并且因地区、种族和收入不同,

实际应用也是有很大差异。

关注“胡迪医学”,了解更多世界医学动态

精准医学面临的挑战有哪些?

精准医学的许多进展

尚未进入临床应用的原因,

主要是临床对精准医学的共同质疑。

大家共同持有的想法认为,

精准医学目前处于转化阶段,

缺乏标准的结果来定义临床益处。

此外,

许多大型临床试验缺乏足够的比较对象,

而发展的快速度意味着许多试验

在报告时往往已经过时了。

篮子、伞和其他自适应设计的引入

是有帮助的,但增加了复杂性。

帮助指导临床医生选择测试和

应用临床检测结果时,

缺乏很好的决策支持工具。

难以提供足够的IT基础设施,

也可能妨碍临床使用。

竞争激烈的市场和制药公司的兴奋点,

使人们更关注技术突破而不是卫生政策。

对精准医疗实施的研究不足,

导致宣传与患者实际疗效之间存在差距。

如何解决精准医学的实施问题?

针对癌症精准医学带来的光明前景,

目前已有几个国家启动了国家举措。

2015年,美国发起了“All of Us”项目,

该项目远远超出了癌症诊疗的范畴。

该项目旨在招募100多万人,

从基因测序到医疗记录,

收集使用10年以上数据。

澳大利亚基因组健康联盟

是一个框架组织,

旨在改进基因组学在临床的应用,

包括为临床医生提供

如何使用检测结果的建议。

比利时、挪威、爱沙尼亚、法国和

以色列也制定了类似方案。

关注“胡迪医学”,了解更多世界医学动态

然而,这些项目中有许多试图

协助实施基因组学,

在提供现有技术教育的同时,

可能难以整合最新的技术。

这些全国性的巨大努力

令人兴奋,并吸引了人们的注意,

但风险是,在一些基础研究实践上,

科学家和临床医生之间缺乏外部合作和协议,

从而出现了多重努力,

阻碍了对患者的好处。

与许多新的医疗方法一样,

高收入国家和低收入国家之间

在获得新医疗方面存在不平等。

这种差距基于一种错误的信念,

即低收入和中等收入国家需要

花费太多资源,来实施这些新型的技术。

精准医疗代表着一系列层次的技术,

包括大数据和基因组测序。

巴西、中国和印度等国家

在这方面已经拥有很多经验和能力。

利用基因检测和大数据能够

更有效地利用现有资源,

可以在低收入或中等收入地区

通过合理的投资和优先次序

获得切实的成果,

但到目前为止,

这种情况还没有发生。

一种更精确的药物,

在减少不良事件的同时提高治疗效果,

当然是我们希望达到的目标。

过去20年大家只是受到

先进科学概念上突破的影响,

但是,没有对实施精准医学

需要的基础设施

和对病人医疗带来的实效性,

给予足够的关注。

精准肿瘤学将继续提供科学进步,

但要为患者创造有意义的诊疗变化,

需要国际间的多种多样的合作研究,

并为病人提供超越实验室的整体治疗方法。

癌症诊疗体系建设远远超越了

癌症治疗的本身。

关注“胡迪医学”,了解更多世界医学动态

声明:本文系健瑞宝医疗整理创作,如需转载请取得许可,转载时注明出处。本文属医疗技术讲座性质,不应被视为任何医疗建议或治疗方案,如您需要,请咨询执业医师。刊载上述内容,“胡迪医学”尊重信息出处的原意,对文中陈述、观点和判断保持中立,不对所包含内容的准确性、可靠性或完整性提供任何明示或暗示的保证。如果您认为文章内容或者来源标注与事实不符,请告诉我们,我们将与您积极协商解决。谢谢大家关注"胡迪医学"。

文章中图片和相关数据来自互联网,图片及资料版权归原作者,如有异议,请及时和我们联系,我们尽快协商解决。

引用柳叶刀期刊社论的来源:

EDITORIAL| VOLUME 397, ISSUE 10287, P1781, MAY 15, 2021

20 years of precision medicine in oncology

The Lancet

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01099-0

In the 20 years since the publication of the first draft of the human genome project, the use of genotyping and genomics have become part of standard treatment for some cancers. The desire to go beyond blanket, and often difficult, treatments for patients to a more refined, efficient, and patient-centred approach is an ideal that is hard to oppose. But as precision medicine in oncology expands to include big data, proteomics, transcriptomics, molecular imaging, and more, there are serious challenges ahead to translate that ideal into meaningful and equitable health care for patients. Issues surrounding rising costs, adequate clinical trial design and data, regulation, defining meaningful benefits to patients, and equity remain to be solved.

The US National Cancer Institute's definition of precision medicine is “a form of medicine that uses information about a person's genes, proteins and environment to prevent, diagnose and treat disease”, although stakeholders' definitions vary widely. Targeted drug therapy is in clinical use for many solid and haematological cancers, as are precision approaches to radiotherapy and surgery. However, even for more established genetic tests, translation into clinical care has lagged behind scientific discovery. Guideline-recommended testing is often underused and varies by region, race, and income.

Many advances in precision medicine have not made it into the clinic because of common challenges to the field. For ideas currently in the translational phase, there is a lack of standard outcomes to define clinical benefit. In addition, many large clinical trials lack adequate comparators and the pace of development means many are often out of date by the time they report. The introduction of basket, umbrella, and other adaptive designs are helpful but add complexity. A lack of decision support tools to help guide clinicians with the choice of tests and application of results, and difficulty with providing sufficient IT infrastructure, may also hamper clinical use. A highly competitive market and excitement from pharmaceutical companies puts a focus on technological breakthrough rather than health policy. Insufficient research into the implementation of precision medicine has resulted in a gap between the hype and the material gains in outcomes for patients.

Several national initiatives to deliver on the promise of precision medicine in oncology exist. In 2015, the USA initiated the All of Us project, which goes far beyond cancer care. This project is designed to enrol more than a million people and use data over 10 years, from genetic sequencing to health-care records. The Australian Genomics Health Alliance is a framework that aims to improve the translation of genomics into the clinic, including advice for clinicians on how to use results. Programmes are also in place in Belgium, Norway, Estonia, France, and Israel. However, many of these programmes try to assist with implementing genomics and might have difficulty incorporating newer technologies while providing education on established techniques. These vast national efforts are exciting and attract attention, but there is a risk that insufficient external collaboration and agreement among scientists and clinicians on some of the basic research practices replicates efforts and hinders the benefits to patients.

As with many new medical treatments, there is inequity in access between high-income and low-income countries. The determinism that is relied on to justify this disparity, based on a belief that some newer forms of technology require too many resources for low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) to implement, is a fallacy. Precision medicine represents a hierarchy of technologies, including big data and genomic sequencing, which many LMICs—eg, Brazil, China, and India—already have experience in and capacity for. Use of genetic testing and big data to more efficiently use existing resources could see tangible results in these regions with reasonable investment and prioritisation. But thus far, this has not occurred.

A more precise medicine, which minimises adverse events while enhancing therapeutic impact, is of course the desired goal. But the past 20 years have been coloured by advanced scientific conceptual breakthroughs without adequate focus on the basic building blocks of implementation and the practicalities of patient care. Precision oncology will continue to deliver scientific advances, but to create meaningful changes for patients, international collaborative research and a holistic approach to the patient that goes beyond the lab are required. Cancer care is much more than cancer treatment.

关闭